The story of the 1960s idea that predicted the future – and the explosive scandal that ended it

For a hundred years, our region was the steel capital of the world. Steel forged in Tees furnaces found its way into the Sydney Harbour Bridge, and weaved across the Victoria Falls. When Churchill’s war cabinet met in their underground bunker, or when the ball hit the net at Wembley, it all happened under structures of Teesside steel. Our region has a proud industrial heritage – before steel, it was shipbuilding at Smith’s Dock, and after, it was chemicals at the Imperial Chemical Industries site. With high wages and good union jobs, in the 1960s it was classified as one of the best places to live in the UK.

But from the 70s onwards, we were ravaged by deindustrialisation. Between 1970 and 1985, a quarter of all jobs disappeared – and in the 90s, automation shrank the chemical industry too. Smith’s Dock launched its final ship in 1986; ICI left Teesside in 2007. The final nail came when the Tories’ apathy over Chinese steel dumping shut down the SSI steelworks in 2015. Three thousand people in my hometown of Redcar lost jobs, and almost two thousand children here now rely on foodbanks each year. Today, Teesside has amongst the highest poverty rates in the UK. Life expectancy is the lowest in Britain and going backwards. Youth unemployment is double the national average, and we have the highest suicide rate in the country. Shuttered shop-fronts line the high streets, at the highest rate anywhere in Britain. Not to mention the Boro were relegated.

This is our piece of the story that played out across the old industrial North. In our thriving golden age, when we were forging structures across the world, nobody could have imagined the decline that was to come.

Except, in the 1960s, one man did.

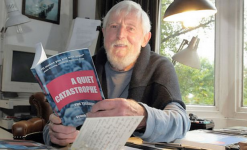

Frank Medhurst was a former WWII RAF pilot, who used his ex-service grant to study architecture and planning. It had been an exciting moment to become a planner – a field of post-war hope, bold dreams of building a better Britain. In 1965, he was headhunted to lead the Teesside Survey and Plan; it was to be Britain’s first sub-regional planning study.

What followed was something radical, not just on Teesside but anywhere. Frank’s team changed the idea of planning. They got out from behind their desks and drawing-boards, and into front rooms around the area. They held 110,000 interviews with members of the public. For the first time in their lives, the people of Teesside were being asked what they wanted their future to look like.

View attachment 24103

The team drew up a forty-year plan, anticipating the changes that were to come and the actions that would need to be taken. They predicted that the two massive industries that kept Teesside afloat – steel and chemicals – were heading for decline. They expected that a wave of mechanisation and changing markets that would cut jobs, and that Teesside would need a broader, more diverse economy to cope.

The first 25 years of their plan would have updated Teesside to Britain’s average. The team highlighted poor housing, schools, employment, infrastructure, and an “appalling” environment. They drew up a pollution report, uncovering a major environmental crisis for standards of living. They exposed extraordinary levels of grit and dust in the smoggy air; while the average amount for rural Britain was 1.5 tonnes per square mile, here it was 235.

After a programme of social and economic renewal, the next 15 years would have developed an innovative modern region. Instead of a string of post-industrial towns, Teesside would become one long, linear city, fifteen miles by four miles, spanning the river Tees. The river would be its backbone, and a fast, modern public transport system would zip along it. Frank recommended that the transit system be ‘enjoyable and free’, facilitating a phasing-out of cars.

Middlesbrough, with its links to the A66 and the A19, would be the economic centre of the region. Stockton would be a pedestrianised historic quarter. Redcar would be a leisure hub. Each would have access to open country; the drama of the North Sea coast to the east, the rolling hills of the Yorkshire Dales to the west, and the vast, wild purple of the North York Moors to the south.

Every centre would be designed with people in mind. There would be open community spaces for socializing, and urban spaces for strolling through and admiring. Routes would be accessible for disabled people, as well as encouraging cycling. The residential area would be at the southern end of the city, away from the heavy industry and smog; it would benefit from landscaping, high tree cover and a favourable wind direction. Land dominated by car parks and low-rise buildings would be returned to community food production and leisure – with allotments, parks and woodland.

It sounds like a utopian 1960s comic book or episode of Tomorrow’s World, but in reality it was a meticulously budgeted and mapped-out plan. It was flexible and innovative – with multiple possible futures programmed onto computer tapes, so that if there was a change in government policy or the regional economy ten years down the line, the local authority need only punch it into the plan to find a range of alternatives that still met the broad targets.

This technological element was far advanced for the time. The scene is comical now. Only one computer in the country was available for programming, the size of a laboratory, in Birmingham. The team had a dishevelled mathematician called Ernie Stringer, who travelled there for midnight every night – the only slot they could book. He would return the next morning with pages of data and in a state of complete exhaustion.

The whole of Frank’s team were similarly dedicated to the vision he was building; by January 1967, nineteen months after they first set up office, the final draft was complete. But the team planning forty years ahead for Teesside couldn’t foresee what the immediate future would bring.

In early 1967, Frank brought the draft report before a panel of senior figures in Government. The meeting was short: they fired him on the spot. These were the days before employment tribunals for wrongful dismissal; they gave no reason, and didn’t have to. He would later tell that if he had refused to go quietly, they had threatened that he would ‘never again obtain professional work in this country’. A statement was issued to the press that he had left amicably.

So ended the first and last effort in British regional planning for half a century. The name behind the move wouldn’t be revealed until several years later: John Poulson.

Poulson was a Trump-like figure, whose father set him up in the architectural business with extraordinary wealth and little knowledge. Between the 60s and 70s he amassed a web of corrupt transactions, involving dozens of councillors and MPs across the country. Teesside alone had 32 elected officials on Poulson’s payroll, in Redcar, Middlesbrough, Stockton and Eston. He spent years bribing council officials for building work. He promised quick and dirty developments – sketch plans within a fortnight, job done within the year. In Stockton, he oversaw work on the Castlegate Shopping Centre, which the town is still trying to demolish today. It was built backwards, blocking the view of the river.

On 22 June 1973, Poulson was arrested and charged with corruption. Many of his contacts were jailed or implicated too. Tory deputy leader and Home Secretary Reginald Maudling, tipped as a future Prime Minister, was forced to resign. Labour’s Dan Smith, a Newcastle councillor, was jailed. Teesside Mayor and leader of Middlesbrough Conservatives, J.A. Brown, was tied to the scandal – having simultaneously been a Poulson advisor for the best part of a decade.

Frank would never see his vision for Teesside fully come to life. In 2018, he passed away, aged 98. A diversified economy remains far off; in our postponed mayoral election, the incumbent Conservative candidate’s central pledge is to ‘bring steelmaking back to Teesside’, five years after his party let it go. So, too, is the pipe dream of fast, free public transit infrastructure. We’ve only just started to move on from the late, leaking Pacer trains – a 1980s bus body bolted to a freight wagon. Dozens of our bus routes have disappeared, replaced by ‘on demand’ services, with Arriva’s cuts isolating whole villages.

It’s not too late for Frank’s values and work to live on, though. We can have greater devolution, new community spaces, and modern infrastructure. We can tackle inequality, and bring good green jobs. The pandemic has demonstrated how rapid economic change is possible, and how essential our lowest-paid workers really are. As we look to the post-pandemic future, we can link up our isolated villages and towns with a plan for the 21st century. But just like Teesplan, it probably won’t come from politicians; it’ll have to come from us. And, unlike Frank, they’ll never see it coming.

Article By Luke Myer