Today we all Take it almost for granted that we can go to a library and borrow a book of our choice. But this was not always the case – indeed there was not a great deal of provision made for cultural activities in the early days of the new town of Middlesbrough. It was almost ten years before the founding by William Taylor in 1840, of the `Mechanics Institute, one of the first institutions to act as an agency for ‘instruction, improvement and amusement of the workers.’ The initial meetings were held in a room in East Street with the guidance of first president, Isaac Wilson. By 1844 a library committee was overseeing the provision of reading facilities – though the number of books available were few.

In 1859 the foundation stone was laid for a permanent building in Durham Street and with a Polytechnic Exhibition, held in that year, helping to raise £2000 towards costs, the Mechanics Institute in its new location, opened to the public on 18 January 1860. The new building soon helped to make the institute the centre of Middlesbrough’s cultural life.

During the 1860’s, helped by the Public Libraries Act 1855 and 1866, Free Libraries opened in many towns and cities throughout the country. Middlesbrough followed suit after R.L. Kirby called a public meeting in the Oddfellows Hall 23 November 1870 to adopt the Public Libraries Act. This allowed the town to take over the Mechanics Institute library of 1,740 volumes on 2 February 1871 and establish a Free Library. A reading room was opened on 3 April and Middlesbrough’s first Free Library opened to the public on 24 July 1871 with William Sterzil as the first librarian – a post he would hold for almost twenty years.

At a time with growing emphasis on literacy for all, the importance of the Free Library services cannot be overstated. Many families struggled to cope financially and buying books or other reading materials was not a priority. Thus, the library service proved to be very popular and was rapidly expanding; a branch reading room open seven days a week was started in February 1872 at Granville Terrace, Newport Road on the corner of Newport Crescent. The Durham Street premises were soon outgrown, and the Free Library Committee recommended at a council meeting 13 February 1877 that the whole library be moved to a new location in Newport Road, at a rent of £120 per annum, with the reading room at Granville Terrace closing – though a reading room remained open in Durham Street.

The new facilities were a great improvement on the previous premises. The reading room was much larger measuring 17m by 12m, well-lit and well ventilated. The principal newspapers were placed on a stand running down the centre of the room with desk tables placed around the sides containing periodicals, reviews etc and reference books. The library too was much improved in size being 8m by 8m and could be reached by borrowers without having to disturb those using the reading rooms. Most important though the increased accessibility to those using the service – seventy-five per cent of borrowers lived south of the railway where the new facility was located. Expenditure in 1877 was approximately £800 with 7,140 books in total and 65,701 issues made that year.

On 10 October 1887, fifteen months before the new Town Hall was officially opened, the library moved again, this time to rooms in the new municipal buildings, on the corner of Russell Street and Albert Road. However, some troubled times lay ahead. In October 1889 there was a special meeting of the Free Library Committee to examine an alleged discrepancy over the number of books declared in stocktaking as well as the general condition of the books, general disorder and untidiness found in an inspection of the library. This resulted in the immediate dismissal of the librarian William Sterzil. In his defence it has to be said that he was very ill and he died 10 December aged 55.

The Free Library received 444 applications for the post of librarian – which carried an annual salary of £104. Mr Baker Hudson was appointed, but he faced immediate problems. A report prepared in early November 1889, found that a considerable number of books were beyond repair and unfit for use. Furthermore, they couldn’t be replaced because of a lack of funds – a situation which had apparently existed for two years. The report stated that the responsibility for this lay with the Town Council and not the Free Library Committee.

The relocation to the municipal buildings had been disastrous too. There were problems with the rooms being used – there were ventilation issues in the reading room both during the day and after the gas lights had been lit. The financial position too was very precarious. The income for 1888 was £907.14 but the outgoings were £1365.92 – a debt of £458.78 and clearly there wasn’t enough money to justify the buying of any books. The expenditure on books had been decreasing in any case; the £382 which had been spent on the buying and upkeep of books in 1885, was reduced to £158 in 1888 and now in 1888 to only £93.

A library without new books?

Public opinion towards the library was positive. The Daily Gazette stated on 27 November 1890 that it was hoped the library would not have to restrict in any way, the ‘diffusion of knowledge…. they have made with advantage to the community’. But clearly things had to change; among several modifications was the closure of the Durham Street Reading Room and the money available from the Council was increased. With an eye to the future, it was decided that from January 1891 the Library Minutes would be submitted monthly and confirmed or otherwise by the Town Council.

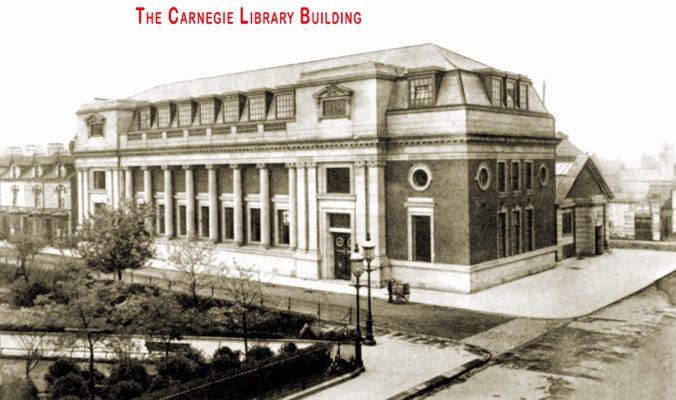

Undoubtedly the library service in Middlesbrough prospered from this point onwards culminating in the opening of the Carnegie Library in 1912.

A Free Library with no money to buy books would never happen again.

Would it?

Paul Menzies